Despite the catastrophic job destruction and over a million deaths worldwide, banks were able to avoid the pain and agony caused by COVID 19. Albeit market turmoil for a few weeks in March, there never seemed to be anything that would endanger the world’s mightiest financial institutions, not nearly to the effect the way that subprime mortgages cooked them 12 years prior.

Was there an explanation for this successful endeavor? The Federal Reserve.

Starting in March, a series of emergency measures were rolled out that temporarily eliminated or blunted restrictions on bank balance sheets, along with ramped up support for financial markets in the US at unprecedented levels.

Risky Finance (who provides visualization tools based on rich financial datasets) joined forces with Washington DC-based advocacy group Americans for Financial Reform (a nonprofit organization which advocates for financial reform in the United States) to analyze some of the impacts COVID-19 had on the six biggest US banks, and how they were able to mediate them with the help of the Federal Reserve.

They key limiting constraint for most these banks is the mandated SLR, the supplementary leverage ratio (which measures the amount of capital a bank has relative to its assets, though doesn’t measure risk). For example, for every $100 of assets on its balance sheet, regardless of its risk, the bank needs to have $7 of capital. The Federal Reserve sets the regulatory minimum SLR at 5%. At the end of June, the top six banks had an average SLR of 7%, comfortably far from the minimum. Though many of the risk models are done in-house, and the banks may have more incentive to take on more risky profits, in expectation of a higher return.

Though, without three critical forbearance measures, some banks such as Citigroup or Goldman Sachs would have been just 30 basis points away from the minimum, which would prompted the Fed to restrict their trading and lending activity.

The forbearance measures increased the numerator of the ratio, the Tier 1 capital of the bank, while another reduced the denominator, the leverage exposure measure. Banks had much less leverage compared to during the early events of the financial crisis. Though, by reducing the denominator, the leverage exposure aspect, the regulatory balance sheets of the six banks fell by almost $3 trillion.

These measures alone allowed the banks to keep lending and trading in the face of the pandemic, keeping liquidity high in the system and continuing to provide credit to households and businesses.

That followed the Fed’s move in March to allow US banks to delay the impact of IFRS 9 current expected credit loss estimates on their CET1 capital (accounting fairy dust). Even though the six banks have collectively increased CECL by $58 billion this year, a resulting $20 billion reduction in their CET1 has been postponed as a result of the Fed’s decision.

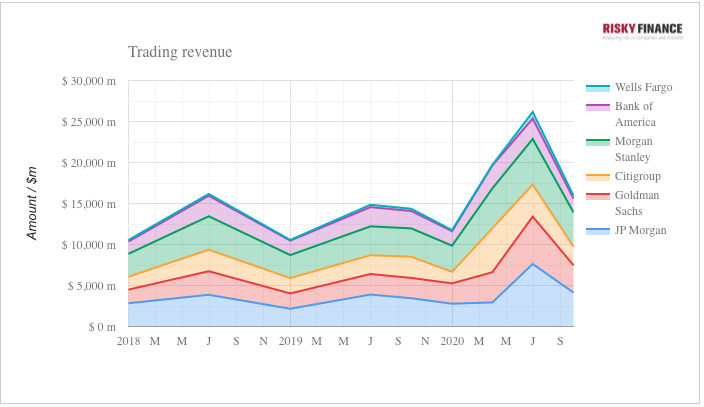

However, the most impactful measure on the banks operations, and perhaps the most controversial, was the Fed’s buying of $3.5 trillion of bonds, including corporate bonds. This had the effect of compressing credit spreads and suppressing volatility. That allowed banks to make massive trading revenues, which we can see in the chart below.

In analysis done by Americans for Financial Reform (AFR) and Risky Finance, they found that in the absence of regulatory intervention, the banks might have suffered trading losses.

If emergency action by central banks normalized the markets, you might expect the banks’ trading revenues to be at a ‘normal’ level too. But that is not what ended up happening.

Spear headed by JP Morgan and Goldman Sachs, the six banks collectively made $19 billion of revenues in excess of this average in the first three quarters of 2020. That wasn’t all. Buoyed by Fed support of the market, by the middle of the year the banks were able to offload corporate loan exposure that otherwise would have stayed on their balance sheets.

This appeared as a bonanza in investment banking revenues (despite most bankers working from home), which exceeded the average by $4 billion over the same period. Combined with trading income, this amounts to $23 billion of excess revenues, which directly flows into capital as retained earnings, and can then be used to bolster share buybacks, dividends and bonus payouts (stocks only go up, remember).

It seems the the Fed does more than just money print, helping avoid a full-blown financial crisis during the pandemic.

Though the question remains, if the position of the banks was so weak going into the pandemic that $3 trillion of support (direct and indirect) was needed to protect them, should capital requirements on banks go further than 7%? Or, should the SLR ratio be re-imagined, or even more extreme, should capital levels in the capital system be raised to guard against any further problems.

Works Cited:

https://www.zerohedge.com/markets/how-covid-forbearance-gave-banks-three-trillion-dollar-boost